Step into a world where light itself becomes a building material, where walls dissolve into shimmering visions of gold and celestial blue. This was the world of the Byzantine Empire, and its most breathtaking artistic achievement was the mosaic. Far more than simple decoration, these intricate artworks were designed to transport the viewer from the mundane earthly realm into the very presence of the divine. They were sermons in stone and glass, telling stories of faith, power, and eternity on a monumental scale.

The art of mosaic wasn’t invented by the Byzantines; they inherited it from their Roman predecessors. But while the Romans favored durable stone tesserae for floors, depicting scenes of mythology and daily life, the Byzantines took the art form in a new, vertical direction. They covered the vast walls and domes of their churches with mosaics made primarily of glass, creating interiors that glowed with an otherworldly light. This shift from floor to wall, from stone to glass, was a revolution in both technique and purpose.

The Secrets of the Shimmering Surface

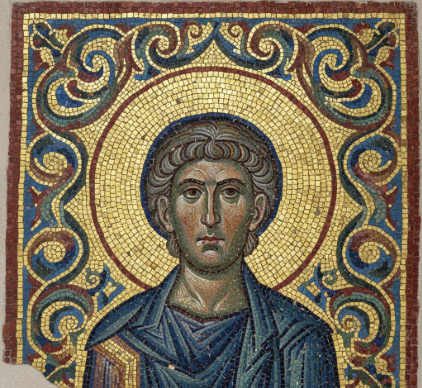

What gives Byzantine mosaics their unique, living quality? The magic lies in the

tesserae—the small, individual cubes of material used to create the image. Unlike the perfectly flat surfaces of Roman mosaics, Byzantine artisans intentionally set their glass tesserae at slight angles to one another. This uneven surface catches and reflects light from multiple directions as the viewer moves through the space, causing the image to flicker and shimmer as if alive.

The materials themselves were chosen for their luminous properties:

- Smalti: This was the name for the colored glass paste, which could be produced in an astonishing range of vibrant hues, from deep cobalt blues and emerald greens to rich reds.

- Gold Tesserae: The iconic golden backgrounds were not made of solid gold. Instead, artisans would sandwich a delicate leaf of gold between two layers of clear glass. This not only protected the precious metal but also magnified its reflective brilliance.

- Stone and Marble: While glass dominated, natural stone was still used, particularly for depicting faces and hands, where its more subtle, opaque quality could create a sense of flesh and form.

This combination of angled placement and reflective materials transformed cavernous, candlelit church interiors into dazzling, immersive environments. The golden backgrounds were not meant to represent a real sky but rather the eternal, uncreated light of heaven itself.

Imperial Power and Divine Glory in Ravenna

While the heart of the empire was Constantinople, some of the best-preserved and most famous examples of early Byzantine mosaic art are found in Ravenna, Italy. This city served as the western capital of the empire in the 6th century under Emperor Justinian I, and its churches are a testament to his ambition to project both imperial authority and Christian orthodoxy.

The Basilica of San Vitale

Inside the Basilica of San Vitale, two iconic mosaic panels face each other across the apse. One depicts

Emperor Justinian, clad in royal purple, holding a golden paten for the Eucharist bread. He is flanked by his court officials, soldiers, and the local bishop, Maximian. The figures are formal, frontal, and seem to float against a golden void, emphasizing their symbolic, rather than physical, presence. Directly opposite, his wife,

Empress Theodora, is shown with her own retinue, holding a chalice for the wine. She is adorned with magnificent jewels, and the detail in her robes is astonishing. These panels are a powerful statement: the emperor and empress are presented as God’s representatives on Earth, participating in the sacred liturgy for all time.

The gold tesserae used in Byzantine art were a marvel of craftsmanship. Artisans would lay a thin sheet of gold leaf onto a slab of clear glass, then fuse another thin layer of glass on top. This process created a durable, brilliantly reflective tile that symbolized the divine light of heaven. The slight imperfections and bubbles in the glass added to the shimmering effect when seen from a distance.

Byzantine mosaic art was not static; it evolved over the centuries. Early works from the age of Justinian, like those in Ravenna, are characterized by a sense of formality, grandeur, and hieratic stillness. The figures are often elongated and appear weightless, existing in a spiritual realm rather than a naturalistic one. The focus is on clarity, symbolism, and the projection of power.

After a period of iconoclasm (the destruction of religious images), mosaic art returned with renewed vigor in the Middle Byzantine period (c. 843-1204). The style became more fluid and emotionally expressive. Perhaps the greatest example of this later style is the stunning

Deësis mosaic in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (modern Istanbul). Here, a monumental Christ Pantocrator (Ruler of All) is flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, who intercede on behalf of humanity. The faces are rendered with incredible subtlety and pathos. You can see a profound sadness and compassion in Christ’s eyes, a gentle sorrow in Mary’s face. The tesserae are much smaller and more finely blended, creating a painterly effect that conveys deep human emotion while still retaining a sense of divine majesty.

The Legacy on Walls

The influence of the Byzantine mosaic tradition was immense. It spread throughout the Orthodox world, to Kievan Rus’ (modern-day Ukraine and Russia), Georgia, and the Balkans. It also had a profound impact on the art of medieval Italy, particularly in Venice and Sicily, where Byzantine artisans were often employed. The glittering gold mosaics of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice are a direct descendant of this tradition.

To look upon a Byzantine mosaic is to see more than just a picture. It is to experience an environment carefully engineered to inspire awe and devotion. It is an art form where humble materials—sand, soda, and metal—were transformed into a radiant spectacle of shimmering light, telling timeless stories of faith on walls of gold.